|

|

|

|

When a supporter of our newsgroup recently challenged us to write about the highly-touted strength and resilience of Texas women, we at first were daunted by a theme so expansive, yet ephemeral--but we were intrigued. So we took it on. But where would we find that strength, discover those women?

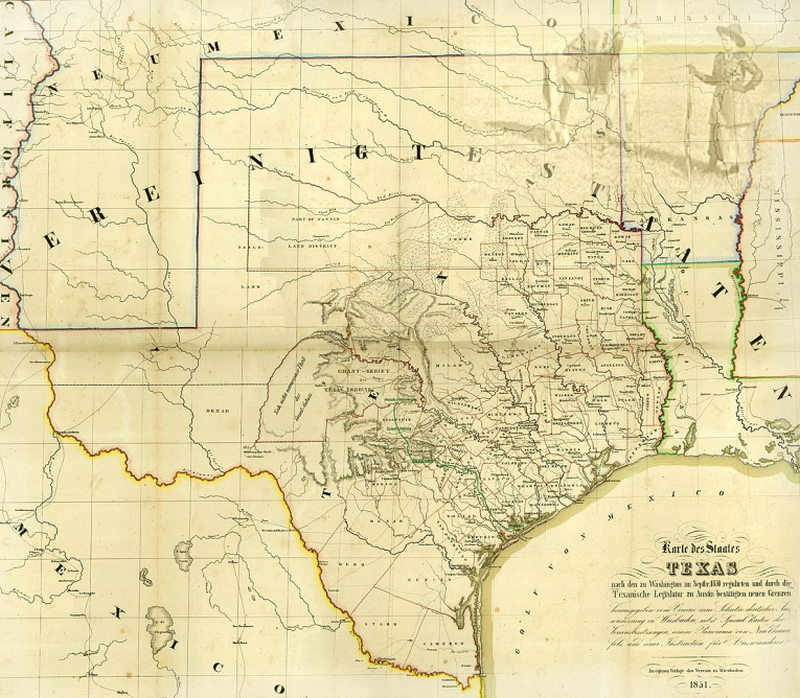

When we surveyed history, we learned, not surprisingly, that women in Texas have always played a signicant role in their communities, as far back as the 1500's (and even before), sometimes working alongside men, other times successfully competing with them:

Like the Caddo interpreter at the heart of negotiations on the Texas frontier, arbitrating among Spanish, French, Mexican, Anglo, and indigenous peoples; a German immigrant cattle baron (our quote above from 1850 is hers); a 19th-century African-American novelist, working in the fields by day, writing by candlelight at night; an even earlier Mexican-American entrepreneur who founded and operated the largest general mercantile store in San Antonio; a widowed central Texas land grantee of humble means who donated 500 acres of her land to found a town; another single woman with no family support who survived Texas's brutal fence-cutting wars to thrive in frontier commerce; a wealthy heiress who gave up her entire sizeable dowry to establish a south Texas town, school, and church.

And many, many more, too numerous to include here. The truth is, exceptional women have always been there in Texas, some unknown to history, others who came to fame. And we revere them all.

With that history as part our vision, we took note of the large cadre of women mayoral officeholders scattered throughout Texas history, but chose to anchor our report in the here and now, and with an alternative point of departure:

Leave the TV cameras and daily headlines to others, we decided, away from Big Box news and statewide plaudits and the national media.

Go to the little Texas towns and cities instead, and find those who exemplify the strength that Texas women are known for, women whose voices seldom reverberate beyond the city limits.

And find them we did--a veritable kaleidoscope of women from every walk of life, most with no thought for themselves, working for little or no salary, a majority with major responsibilities to other jobs and concerns, and for no better reason than that something needed to get done to support their people.

After our months'-long queries, we chose to chronicle the lives, careers, hopes, ambitions, challenges, and dreams of today's women mayors of Texas--and they truly inspired us.

We think they will inspire you, too.

Getting this important story out was one of the most challenging projects of my career, not only due to its scope--we interviewed upwards of 20 mayors (and counting) for it; but also because of the demands on interviewees' time and attention--not unlike the proverbial herding of cats. But in the end, mostly owing to their generosity, we are able to bring out a significant story about the significant people that they are.

Finding, interviewing, and writing about the women included in this piece also taught me that the legend is real: Texas women really are uncommonly strong--and exceptional. It's in their genes.

And at least where the cohort of women introduced here is concerned, I can report Texas is in good hands.

For those who relocated here from other places and also came to serve in office, we see that they have been warmly welcomed. You don't have to be born here to be a Texas woman.

These women also inexplicably drew me back to my own Texas cultural bedrock; because our paths, though as varied as the stars, come from a common store of meaning and identity that not even the harshness of today's political discourse can tarnish.

Some days, The clink-clink, clink-clink, clink-clink of the blades twirling, the ratcheting whirr of the tail swinging around to face into the wind. And when I do, I find myself looking up at the windmill by the wellhouse on my grandmother's back property. Then, the empty space displacing this palpable memory jars me awake. I long to get up from the old oxidized lawn chair on that dry-hot summer day in Texas, go pump the handle next to the mill, and fill a tin cup when the ice-cold water comes bubbling out, but I can't. The windmill has been hauled away now, the wellhouse long torn down, the garden the water sustained reverted to bleached stalks and whorled dust. And the people--the old people. Where are they? Chastened, I start to wonder if the memories of our distant Texas forebears are like that: old windmills still whirling, still drawing water, spinning out stories, impelling lives. Who knows where they've gone? Somewhere, our grandmothers still stand in the searing Texas heat over an iron kettle simmering with soap and water, raking a shirtsleeve across a washboard, then looking up in our direction, and vanishing. Did they see us? Or we them? Carried aloft on the perpetual Texas wind, now they move easily through time and space, those imposing figures standing firm against the harsh Texas landscape. Texas writer Mimi Swartz once opined that we who endure this hermetic modern era may never again see the likes of the larger-than-life Texas women of near and distant history who commanded the times they lived in. I don't know, Mimi. Texas women today are certainly afforded more public opportunity, and many of us aren't as materially constrained as our foremothers were in their time. But if putting this story together has taught me anything, it's that something persists--something inviolable--a burning line dissolving time, binding them to us, out under the winking stars of the Palo Duro, while the fire crackles and a coyote sings. I can feel it. I can feel them. And so, I think, can the pioneering women whose lives and careers we herald here.

I have lived all over this world, and I won't say there aren't legions of women everywhere, in every time and space and social setting, hopeful but often alone, laboring for their people. But I will say this. If I were charged with raising an army to defend a life-or-death cause, I would get a bunch of Texas women together and tell them: Here's the mission, and it has to get done. I can't offer you much money, or any supplies, or recognition, or fame, and you're going to get cold and go hungry, and you might get yourselves killed, and ... And before I would finish the harangue, they would all have scattered to the four winds, each already hard at work at the particular task that only they can do, and that the world needs for them to do. And heaven help the men who would try to stop them. |

|

|

|

"Texas is heaven for men and dogs," an exhausted frontier woman told memorialist Noah Smithwick in 1830, "but hell for women and oxen." As a young man, Smithwick had travelled to Texas from his native Tennessee in the mid-19th century to find adventure and seek his fortune; and as a writer he was an astute observer of all he encountered, including the lives of women, whose labors' status all stood secondary to the activities of their men. "Texas men talked hopefully of the future; and children reveled," Smithwick wrote in his diaries. "But the women--ah, there was where the situation bore the heaviest."¹ Smithwick clearly felt frontier women's burden.

|

| Well might Smithwick have sympathized with long-toiling frontier women: theirs was the responsibility for weatherizing their families' homes; planting, growing, harvesting, and conserving foods; making soap from ashes and tallow; hunting, butchering, and preserving small game in smokehouses they themselves built and maintained; cutting trees and chopping wood; clearing brush and removing rocks from garden land; carving household items and tableware from gourds, wood, and cane; cooking meals in fireplaces they helped construct; hauling water; scraping, cleaning, softening, cutting, and sewing deer hide together for clothing; washing household items and clothing in iron kettles; defending the homestead from threats by armed resistance when men were absent; bearing and tending children and serving as midwives; nursing the sick and elderly; and feeding and caring for domestic animals--among many other things that might arise, including service to their neighbors and communities. |

| Though their labor served the development of Texas in important ways, the role of frontier women still was limited to what one of the wearier of them described as "All of the work, and none of the say." It was only Texas men, after all, who during the Texas Revolution convened a constitutional convention in 1836 and declared Texas's independence from Mexico; and only men who fashioned a constitution for the fledgling Republic of Texas, electing all-male interim officers until statewide elections were able to be held. Texas women meantime remained on their lands with their children, or fled en masse from insurgents during the Revolution. When Texas joined the Union in 1845, male citizens again quickly formed a state government and established a state Constitution, fashioned after the nation's own; but limited the right to vote to white males over the age of 21, excluding women. It wasn't a lack of desire to enter into public service that kept women confined to their duties in the home, however: it was their lesser stature as citizens as an enduring fact of their disenfranchisement. Texas women's right to vote initially became law in partial measures: first in 1918 when they won the right to vote in primary elections. (With this victory, nearly 400,000 women quickly signed up to cast primary ballots.) Developments later at the national level changed Texas women's right to the franchise even more profoundly. After decades of long and bitter battles, with the passage nationally of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution on June 4, 1919 guaranteeing the right, women in Texas could finally fully vote. The Texas legislature ratified that amendment on June 28, 1919, making Texas the ninth state in the Union, and the first state in the South, to do so. Then the doors to public power for women in Texas began to open. Edith Wilmans, one of the many women of her time who had political ambitions, won her race for Dallas's District 50 of the Texas House of Representatives in 1922 to become the first woman elected to the state legislature, and others followed. Even in pre-suffrage days women had started to compete with men for elected office and step into public leadership in greater numbers: After years of male-only leadership, Ophelia "Birdie" Harwood was elected on April 3, 1917 as the first female mayor of the town of Marble Falls--by an all-male vote. Three years later, citizens of Jewett, Texas, weary of the wheeling-and-dealing among the town's male officeholders, elected Hattie Barnes Adkisson as their mayor, along with five other women as aldermen, the earliest all-woman town council in Texas. But as significant a status as the office of governor would have to wait decades, or, apparently, even longer, to be entrusted to women. Miriam A."Ma" Ferguson served as Texas governor from 1925-1927 and 1933-35, in her first term succeeding her husband, James Ferguson, after he was convicted of malfeasance and impeached. It was not until 1991 that another woman--the eminent Texas stateswoman Ann Richards--was duly elected governor. (Richards was elected Travis County Commissioner in 1976 and Texas State Treasurer in 1983, and served as governor from 1991-1995. She did not win a second term.) In more recent eras, Texas women have more often been elected as mayors of larger cities, with the greatest number formerly proliferating in the 1970's and 80's: In 1975, Lila Cockrell was elected San Antonio's first woman mayor, followed by Adlene Harrison, Dallas's first woman mayor, elected in 1976. Since then, the pace of first-time election of women as mayors in Texas has increased steadily, notably in the terms of Carole Keeton Strayhorn (Austin, 1982), Kathryn "Kathy" Whitmire (Houston, 1985), Ann Pomykal (Lewisville, 1987), Betty Turner (Corpus Christi, 1989), Suzie Azar (El Paso, 1991), and Kay Granger (Fort Worth, 1999). Over time, the number of women being elected for the first time as mayors in Texas's small towns and medium-sized cities has steadily proliferated, albeit glacially slow. Women in Texas today comprise only 12 percent of mayors, despite women's comprising 50.3 percent of the state's total population. Based on our own survey of the cadre of women we interviewed for this edition, and the increasing numbers of women statewide now serving as Mayor Pro Tems, that trend is sure to change. Our own list also shows multiple "firsts" among currently-serving mayors we chronicle here: First woman to be elected mayor: Cuero, Hallettsville, Marlin, Nordheim, San Angelo, Schulenberg; youngest woman to be elected mayor: Leander; first Woman of Color to be elected mayor: La Grange, Marlin; and first Woman of Color to lead an all-minority City Council: Marlin. Please join us as we share the remarkable stories--in alphabetical order by first name--of the women we interviewed for this Feature Edition of Noticias Southwest. Ranging in age from 34 to 87, and representing a vast range of ethnicities, heritages, political persuasions, and professional histories, each governs with her own unique style of leadership--some quietly and gently; others with drive and audacity; but all with good humor and an uncompromising sense of duty, as you will see.

|

|

"If women can hold the family together, why couldn't we hold the country together?"

Hallettsville Mayor Alice Jo Summers and her boy Cisco (Photo courtesy Alice Jo Summers) | |

|

For Hallettsville Mayor Alice Jo Summers, the road from Mom to Mayor is a short one. "I figure if women know how to hold the family together," the twice-serving mayor asserts, "why couldn't we hold the country together?" So great is this long-time mayor's sense of filial love, in fact, that it touches even the critters she fosters on her country property just outside the city. Take her young colt, Cisco. A quintessential Texas woman whose feet are not unfamiliar with a saddle stirrup, Summers speaks affectionately of her beloved equine. ""He was born deep in the night," Summers remembers, with a softness in her voice. "And I was the one who found him--and I picked him up and held him in my lap. So I guess he thought I was his mother, because he started suckling on my fingers." The mare, Cisco's dam, was nearby, Summers says. "His mother was standing right there by me, and when she saw him do this, she came over and got between us." That imprint of the human family imbues all this indefatigable mayor does in, and of, her community, and she reaffirms that value as she moves through her busy days. "Texas women have always known they had to be strong, all the way from the early days," she avers. But this mayor has an historic, and decidedly pragmatic take on the source of Texas women's strength: "Were we, are we strong?" she asks. "Yes! What choice did we have? This is cattle country. With the men gone off, sometimes for months at a time on cattle drives, women had to take charge of everything else--the home, the acreage, the animals, the children, their neighbors, their towns. Women were always full partners with men." It's that family-community connection again, a constant backdrop for Summers. "You can help run your town like you run your family," she asserts, and makes good on her declaration by championing her small, conservative community, always referencing the young. "We've got something good going here," she muses, "something worth hanging onto. "We have a lot of things many towns don't," she goes on to say. "We have a great city park, we've got all the services." A former teacher (she earned a B.A. degree in English from the University of Houston), she worked for Texas state government before retirement, and now also cares for her 97-year-old mother. If seeming economic necessity persuades young adults to seek their fortunes elsewhere, she remains confidant of the pull of Hallettsville's community and family values. "Sometimes kids out of high school leave here and go elsewhere," she muses, "for jobs and such. And then, first thing you know, they're back." Summers--a former city council member and Mayor Pro Tem who went on to be elected Hallettsville's first woman mayor, remains popular, in no small part for her unerring commitment to a people-first sense of service. "For me it's not 'How is this going to affect me'--really, if you're in office, you shouldn't be getting anything out of it at all--it's about the people," she declares. "I always ask myself, 'How would I feel about something affecting me?' and 'How will this affect the people in my town?'" The mayor is quick to assert Hallettsville women's continuing history of leadership. "Men here are very responsive to ideas from women, always have been," she says. "Since 1985 there's been a woman on the city council. So I'm proud of being part of that." Summers presides in a big way over her small town (its population at last Census was about 2,700), and touts its status as a founders' land grant settlement: Named after John and Margaret Hallett, whose family colonized the area starting in 1831 with a grant from Stephen F. Austin, Hallettsville is the seat of Lavaca County. Margaret donated 500 acres of her land to found the new town after the death of her husband, and is herself an exemplar of strong Texas womanhood: Legend has it she defended her frontier home against a native Tonkawa brave and his band by striking him on the head with the flat side of a hatchet, causing a searing wound. Laughing, but understandably respectful now, the young man purportedly left the Anglo family in peace, went back to his village, and told his chief what had happened. As the story goes, the chief was impressed, and gave Margaret the title "Brave Squaw," later supposedly making her an honorary member of his tribe. Interestingly, Margaret also loved and raised horses. Margaret's legend or no, then, it appears this quiet little town on the Lavaca River is destined to foster strong women, from its pioneer founder to those who now call her land grant home, reaching across the years to the present day. "Throughout all I do," says Mayor Alice Jo Summers, "I want to stay strong for my family, my town, my people." | ||

|

"We're totally apolitical here--Potholes aren't Democrat or Republican" Menard Mayor Barbara Hooten (left) with Councillor Collyn Wright |

|

| How'd a military brat, whose childhood took her to many a far-flung place, end up in a pretty little Texas town like Menard--and stick? It's complicated. "My dad was career military, a pilot in the Air Force when I was a kid, so we moved around a lot," long-time Menard Mayor Barbara Hooten recalls. "So I got to see and live in places like England, Japan. Then we eventually came back--to Alabama--and finally settled in various places in Texas." But where's the Menard connection? "Well, I went to high school in Fort Worth, got a science degree, met and married my husband--a pharmacist--and practiced pediatric physical therapy for 48 years. "But then in the middle of all that, we got this phone call," Hooten interjects. Out of the blue, she says, a friend called from a town called Menard, with an interesting question. "She said, 'Hey--the pharmacy here is for sale--would you like to buy it'?" Hooten says. "And I looked at my husband, and he looked at me, and ... we said, 'Uh ... yeah.' And we came over right then." All that was 44 years ago, in1980. And Hooten has lived, worked, and contributed to her historic town and community ever since, never looking back. Joining Menard City Council in 2007, Hooten served for a term as Mayor Pro Tem, and in December, 2007, when the current mayor resigned, she was asked to assume the Mayorship in 2008. She's now served as mayor 16 years. Ever the town booster, this world traveller turned small-town promoter says Menard not only is home, but feels like it, too. "It just feels like home. It's where I want to be. It's where I belong," she declares. Hooten is quick to give credit where credit is due in the smooth functioning of town business, disclaiming any notion she is a solo act. "Yes, I can run a City Council meeting," she asserts, "but I can't run a whole town. No one could. No one should." For that, she avers, she needs her "team." "I have a great team," she shares. "They're the ones who keep the city running." That teamwork showed its mettle, Hooten remembers, during Texas's freeze and disaster of 2021. "For four days during the freeze," she relates, "we all were without electricity--and we had very few generators. But the Fire Department had a generator, and set up cots at the station. Other people had fireplaces, or propane. And so, we weathered it." Hooten goes on to add that hardscrabble learning curve taught her city valuable lessons. "It was hard, but we learned from that, we reexamined, we got grants, and made necessary changes," she states, proudly. "And now we're prepared." These days, Hooten conflabs repeatedly with citizens and local leadership alike, conversations all revolving around a simple question: What's next? "It's not as simple as you might think," she cautions. "We can't do everything we might want, and here's why--water is always a major issue. "The overriding concern in answer to that question has to be, 'What are we going to do about infrastructure?' And at the heart of that is water." Here, Hooten alludes to a Catch-22: "We don't have any money. Our tax base is limited, only 1400 people. So funding is always an issue. "To answer that seems straightforward, but it's not," she continues. "Sure, we'd like to have a hundred more families, but after that, we can't handle it--because of water." In the Hooten playbook, you make do, it seems, with what you've already got--and that takes concerted will. Acknowledging there are always differences of opinion about how things should be done as a community, Hooten praises her town council for their uncommon ability to work together. 'I have to say, on our council, we are absolutely apolitical--we just get the job done," she asserts. "Potholes aren't Republican or Democrat." Menard's easy ambience is drawing new people to town, bringing equally new ideas, she says. "In the last five years, we're seeing young people come here to raise families, and they're just full of energy, new ideas," she says. "And they got to work, too. They built a new playground, cleaned up a park, took part in a new beautification program, and set up an artist's performance space, where people can perform. They said they want the town to be known as a 'music friendly' town." Menard's mayor claims there is no better time to feel the magic of her home town than during the holy season, when citizens drop whatever they're doing to put up Christmas lights. "Oh, but it's during Christmas we really shine, when we set up our beautiful, spectacular Christmas light show," Hooten murmurs, with a warm glow that equals that of the lights she describes. "We go all out for our Christmas light display--it's a tradition--starting with the setup. And our city workers really excel with that. "I've been out and heard them talking as they work. They'll say things like, 'Let's set this up over there,' and then someone else will throw in, 'No, it'll be better over there,' and on and on, until it's perfect." The mayor notes townspeople go to great lengths to involve local children as they launch the season. "I'll go get a bunch of those little unfinished ornaments and take them to the school kids," she says. "And they'll paint and decorate them, and we'll put them up, and they can see what they did when everything is displayed. Then we all get out and just look, and look." Then the lights up and down city central streets glitter and gleam; and the big, bright stars of the Texas night skies twinkle and blink, perhaps in answer.

| ||

|

"I took a lot of heat for things I had no control over" San Angelo Mayor Brenda Gunter (Photo courtesy Joe Hyde, San Angelo Live) |

|

|

Approaching the end of her first term in office, San Angelo Mayor Brenda Gunter in 2021 was, in the words of San Angelo Live's Joe Hyde, "having a hell of a year." The long-time newscaster was referring to a string of catastrophic events that converged almost overnight to lock the central Texas mayor and her administration into emergency response mode, the first coming on during 2021's deadly winter that demanded an unparalleled response from the city's resources. When the winter storms swept Texas during February, all of Texas--San Angelo with it--froze, after the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) power grid failed, leaving millions without heat and power, and bringing on emergency shortages of food and water. (The ERCOT crisis ultimately was blamed on the failure of management to winterize the natural gas infrastructure the entire system depended on, and resulted in upwards of some $195 billion in losses statewide.) "It was a situation none of us had ever lived through," Gunter remembered. "There's no playbook for something like this." And in the face of that unprecedented challenge, Gunter declared she and city staff had to craft an equally unprecedented survival plan. "We decided we had to be a leadership team--to speak with one voice," Gunter recalled. And an immediate plan of action was crafted out of that esprit de corps. Out of the chute, as San Angelo continued to freeze hard under single-digit temperatures, the mayor stressed city leaders' first concern was the immediate welfare of the town's residents. "We moved quickly," Gunter told Hyde. "We wanted to make sure that people had places to turn to, that we didn't have starving people." As city staff scrambled to get emergency measures in place, Gunter herself moved throughout the city, and showed up repeatedly to monitor circumstances at San Angelo's spacious McNeese Convention Center, where scores of residents had come to take refuge from the cold. Greeting each person there (and not a few dogs), Gunter moved through the crowd handing out her cell phone number, and assured one woman whose apartment house had been destroyed by freezing and flooding pipes, "We want you to know we're on this--you're going to be warm, there's plenty of food, and you're going to be safe--the police will be here 24-seven, and so will we. So let us do the worrying--and call me if you have a problem." Stressed humans in the throes of uncertainty and disaster, however, often will assign blame to the very people trying to help, and invariably focus on moving targets. Gunter became such a target. "Yes, it was almost like, Mother Nature was looking to me for guidance," Gunter quipped during her Live interview. But Gunter kept her composure through the freeze, and moved forward as another crisis loomed: As if countering a national weather disaster and having the lives of her own constituents in her hands were not enough, unknown to the mayor and city staff, an environmental time-bomb had begun to tick in a nearby San Angelo neighborhood. Only weeks after the freeze had taken hold in the city, residents of PaulAnn, a rural San Angelo enclave, called in to report their water "smelled like mothballs." The call about the smell had come just 72 hours after the freeze began; and city water department staff hurried to find the cause. After testing the PaulAnn water supply Feb. 8, San Angelo water department officials discovered that acetone, naphthalene, and benzene had not only contaminated water in the PaulAnn neighborhood, but also had been found in water samples citywide. It was suspected that, as temperatures slowly began to rise after the freeze's coldest days, icy pipes in many areas had thawed, causing more breaks in water lines and resulting in pollution. Gunter and city staff now had another urgent health problem, and quickly issued a "Do Not Use" declaration. The February freeze and municipal water contamination notwithstanding, Gunter earlier had been laboring to ameliorate a national health crisis that impacted her city. After the initial nationwide Coronavirus outbreak in 2020, Gunter had been leading recovery efforts locally while striving to persuade her ultra-conservative community to adopt measures to prevent the virus's spread. "I took a lot of heat for things I had no control over," Gunter said in her April Live interview. "We kept advising, 'Wash your hands, social distance, wear your masks,'" she declared, "and they thought it was us--but it wasn't." By necessity striving to abide by state and national mandates, Gunter avered, San Angelo was "being directed by the State government--we weren't given options." Gunter said she kept asking San Angeloans to have civic pride, though, and take individual responsibility for helping protect their fellow citizens, and it seemed to work: Gunter reported at the time that, compared to other regions, San Angelo had fewer cases and less spread of the deadly virus. The mayor said she also drew frequent criticism when the temporary closure of local businesses impacted city revenue. "We had lots of sales tax loss during Covid when businesses had to be shut downtown," she recalled, noting the loss was unavoidable. And she continued to endure frequent critiques of her personally and her purported motives during the closures. "First, everybody thought that I had the authority to shut down all the businesses downtown, and they blamed me when they were. But I had no authority to do that," Gunter said. The long-time owner-operator of Miss Hattie's, a trendy downtown San Angelo restsurant, Gunter noted she also began to hear complaints that her concern for her own bottom line would lead her to lobby for restaurants to stay open during the crush of Covid. It didn't happen. "It wasn't Brenda Gunter wanting to keep the restaurants open," she countered. Gunter gamely presided over her city's three major challenges during 2021 and went on to be reelected in May, but events during her new term in office suggested she would continue to be tested. Starting in September, 2021, promulgators of the so-called "Sanctuary City" antiabortion ordinance journeyed from east Texas to San Angelo to lobby local religious leaders and the City Council to adopt the ordinance solely by Council authority and forgo a public referendum. But Gunter, though a Republican mayor who also had described herself elsewhere as antiabortion, would have none of it. "I believe strongly that seven people should not be making this decision--a population of 110,000 should make the decision," Gunter declared at a September 9, 2021 Council meeting. The ordinance's chief proponent even showed up unannounced in February, 2022 at Gunter's restaurant to pressure her further, and returned to attend a Feb.15 Council meeting. Gunter pointedly reminded him her city's will, not his, was preeminent. "Do you believe, you sitting here today," Gunter hit back, gazing steadily at the young man and his assistant on the front row of the meeting, "that you have the right to speak for all of the citizens? We have elections for this." Gunter at a later date insisted outside parties would not be dictating affairs in San Angelo while she was at the helm. "This is our city, not your city," she reminded the two east Texas men who had again come to town to press their cause at a March 1, 2022 Council meeting. Their group and its allies later accused Gunter of violating Texas's Open Meetings Act and claimed she had been working "behind the scenes" to defeat the measure, but their claims were never proven; and Gunter, with the support of Council, held fast to her commitment to the Democratic process, requiring the group to take the proper measures to get their proposal on an official ballot. Ordinance proponents did, in fact, go on to gather the required signatures to cause a referendum to be held on the issue. And as Gunter herself had predicted, San Angelo voters approved the ordinance in a special election Nov. 8, 2022. | ||

|

"I help whoever needs help. If you need help, I'm going to give you help"lll Former Marlin Mayor Carolyn Lofton | |

| Former Marlin Mayor Carolyn Lofton's kind, quiet voice belies another quality that makes her speaking style so compelling--a sense that things are firmly in hand; that the buck stops here. And as she speaks, listeners can sense just how she has lived, how she has endured, as a Black woman in her native rural Texas: There is pain there, but there is also great faith, great calm, and great attention paid to the inner voice that will guide her through each challenge she faces. Approaching the mayoral election period in 2019, Lofton says she continued to survey the economic and physical deterioration Marlin was experiencing, and determined to take leadership and try to effect change. "I saw that there was a negative aura around us," Lofton muses, "and knew things had to change. I felt like I might be able to help." Lofton in part is referring to the decades-long era of economic stagnation in which her town was plunged when major employers--a carpet manufacturer, turkey-processing plant, and Veterans Administration hospital among them--closed, taking hundreds of jobs with them. But she says she knew her small town's challenges had deeper social causes. Committed to restructuring the city's fiscal records, getting city income and outgo well-documented, and attracting new business to town, Lofton tentatively decided to run for mayor, and accept the increased demands on her time holding the office would make. Still, she wasn't convinced. "I kept having a feeling, like an intuition, that I needed to run," she recalls. "But why me?" A woman of deep religious faith, Lofton says she at first resisted her urge to try for the office. "So I prayed about it," she says, in turn asking, "I need a sign." In the next few days, agonizing over what to do, Lofton says more palpable impressions came to her, originating from beyond her own awareness. "A voice came to me," she remembers, "saying, 'You run. You can do it.' But I wasn't ready yet." The voice, she insists, kept echoing. "Finally, a voice said, 'Turn in the application!'" she declared. "And then I yielded--I went over and filed the paperwork." Lofton ran her campaign on working to create a better economy in Marlin and instill fiscal order and responsibility, and promised to make the town "a great place to live again." She decisively won her race on May 4, 2019, to become the first woman, and first person of color, to be elected mayor in the town's history. At the same time, she became the first person of color in the state to lead an all-minority City Council. In touting plans to create jobs and increase opportunity, Lofton in her campajgn and early administration hearkened back to Marlin's deep historical relevance, when the little town was the locus of vibrant business interests and a nationally-drawn tourist trade, much of it owing to its hot underground mineral springs, discovered in 1892. Marlin's natural mineral well, once the source of vibrant tourist attraction, still flows, with continually-streaming water that hovers around 105 degrees. Tourist trade was in fact so good in the 19th century that Conrad Hilton opened a large luxury hotel in Marlin in 1930 to cater to health-seeking travellers who came to relax, recreate, and bathe in the springs, which were thought to have healing properties. Massages, spa services, and beauty treatments were offered at the hotel, and some upscale homes of that era sported large, elegant swimming pools and bath houses using the spring water. The town in these years also was home to a prosperous Jewish business enclave, operating thriving mercantile, dry goods, and cattle enterprises. When the hot springs era ended, however, Marlin businesses began to close, and the town experienced decreasing economic opportunity--while at the same time problems of racial inequality, present in the area for centuries, persisted. In the 19th century, Falls County, Texas, of which Marlin is County Seat, was settled by people from slave-holding states like Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee, who brought slaves with them to the region. (Population figures from 1860 for Falls County revealed that 47 percent of the county's population--1,716 residents--were slaves.) The area was integrated in 1968. Lofton is herself part of that deep heritage, as are many of Marlin's current residents. She also claims ancient Blackfoot descent from the same frontier era. Joined by a new City Manager, Cedric Davis, a former mayor at another Texas municipality, Lofton says she immediately set about resolving intransigent problems in the city, and tried to create greater economic opportunity. "Nobody would loan us money, our water was cut off, nobody knew where money was going, and finally, they were trying to close our schools--we had to turn that around," she says, and began by engaging a former District schools superintendent to improve educational quality and accountability. Though she was working more than full-time--she has been a social worker for 30 years, is a member of the adjunct faculty at Baylor University's Diana R. Garland School of Social Work, and is on call with several facilities serving regional hospice patients--Lofton began advocating for Marlin in areas that were most needed: She reopened a city park, invited capital funding groups to town to interest them in the city's historical hot springs spa potential; initiated needed infrastructure projects like road improvements; and labored to clean up the city's books. It did not go well. In what some observers described as an attempt at a "hostile takeover" to undermine her authority to bring change, an entrenched cadre of the City Council Lofton says was part of the town's old guard, attempted to defeat her efforts by acting as a quorum, often forcing Lofton to use her mayoral veto power to enact her goals. In the midst of the backlash, both Lofton and Davis were threatened with termination; and when Lofton ran for reelection, she was opposed by an Anglo female candidate, who won the race reportedly by as little as two votes, with nine valid ballots allegedly listed as misplaced. Lofton has contested the election, claiming ballot-tampering; has retained an attorney, and is awaiting a court date. As she waits for her trial, Lofton says people in her orbit ask her if she will serve as mayor again if the election issue goes her way. "I'll wait to see," she says, "and whatever happens in the meantime I will continue to work for my community, and do what I believe we're here on earth to do: help each other." "I help whoever needs help," she says. "If you need help, I'm going to give you help."

| ||

|

"I learned to use the gavel" Floresville Mayor Cecilia "Cissy" Gonzalez-Dippel |

|

| Like many other women serving as Texas mayors we interviewed for this story, Floresville Mayor Cecilia "Cissy" Gonzalez-Dippel has had her share of detractors--starting with her first attempts to bring order to a city administration and Council known for infighting. But Gonzalez-Dippel says she didn't anticipate simple differences of opinion would force her into a lawsuit opposed by her fellow councilmen. "It all started with what I thought was going to be a pretty straightforward concern of getting Floresville's Election-Day date into compliance with state law," Gonzalez-Dippel recounts. "But who could have predicted something this basic would be turned into an all-out war over power?" In complicated and protracted legal wrangling over her entire term in office, Gonzalez-Dippel relates how her initial desire to change her city's election-day date devolved into a rancorous lawsuit and upended city politics. "In the beginning, the Floresville City Council in 2013 had voted to move its election-date from May back to November," Gonzalez-Dippel explains. The problem came, she adds, when the 2019 Council voted to move the date back to May, and missed an important deadline in filing it. "I started getting calls from the State elections people (Texas Secretary of State's Elections Division), saying that wasn't legally allowed," Gonzalez-Dippel adds. And in complication after complication, the mayor watched as the Floresville City Attorney recused herself from issuing an opinion, and the city hiring outside legal counsel to provide an opinion, with inconclusive results. To resolve the issue and bring the city into compliance with state law, Gonzalez-Dippel and allies on the city council filed suit in District Court to compel the proper result, and were upheld, in turn also being upheld at the appellate level during two appeal processes. In a third appeal, however, a new judge overturned the previous decisions, and the case went to the Texas Supreme Court. Hopeful, but wary, Gonzalez-Dippel says no one was prepared for the result. "The court duly noted their busy schedule and the fact it was late in the year," she says. "And pretty much just refused to hear our case." The finding took its toll on an already exhausted and world-weary plaintiff. "Hearing that decision was one of the worst days of my life," Gonzalez-Dippel muses. "Here we had just tried to do the right thing, the legal thing for our city, and were stopped short by those whose duty it is to be fair--it cost me some faith." But the south Texas mayor is no stranger to hardship--and victory over it is, in fact, part of her family heritage. "My dad had a really difficult childhood, and he fought through unbelievable hardship to do something in this world," she says. "My dad knew how to survive." As young boy with a deeply impoverished family, Gonzalez Dippel's father was at times fostered by distant relations, and grew up by fits and starts on the King Ranch, where some of his family worked. Conditions deteriorated so badly that Gonzalez-Dippell's father and his siblings were sent to a home for poor children. Eventually, her father was effectively orphaned and became homeless, wandering, and sleeping under a park bench in Kingsville. "That's when Mrs. Treviño, this beautiful woman, saw him and took him in," Gonzalez-Dippel says. However improbable, these crushing experiences created the power of a dream in the young man's heart, she says. And, as we shall see, a father's far-flung dream imbued his daughter with a dream of her own. Born Alfonso Gonzalez, Gonzalez-Dippell's father ultimately came of age, went into the military, received training in the maintenance of aircraft, and became skilled at--and very fascinated by--one aspect of the crafts' operation. "In his military duties, my dad saw and got involved with all the radio systems," Gonzalez-Dippel recounts. And that's when an expansive dream--his dream of having his own radio station-- was born. "My father, through long, hard work, made it happen," she went on to say. "He tried and tried for 15, 20 years--"He founded his radio station from scratch." Alfonso's home town station, KWCB, went on the air in South Texas in 1978, and became a community voice and source of news and entertainment for a wide audience; and in its success and popularity began to draw in his own daughter, now in high school, as she worked after school and off days cleaning, sweeping, taking out trash, staffing the office--whatever needed doing. "Then my senior year, my dad said to me out of the blue, 'Cissy, you can go on the air.' It startled me." She lacked the confidence, she says, to try it. "Now, at this point I could put the records on the turntable," she laughs, "but going on the air--that was something really different." But try she did, became a skilled radio personality, and credits the experience with bringing her into the public eye. Thereafter, Gonzalez-Dippell moved to San Antonio, enrolled at San Antonio College, and majored in Broadcasting. She used that skill and expertise to move into other areas of public life, including her involvement with Floresville city government. And though it all, though her father died some years ago, Gonzalez-Dippel says her father's example and spirit hovers over all she does. "I credit my dad so much for his success because he had such a very, very difficult childhood," she asserts, "and he continues to inspire me." Gonzalez-Dippel's segue into Floresville politics came when she became a frequent observer of City Council meetings, and people began to notice her. "In 1999, people started telling me, 'We think you should run for City Council,' and, after lots of thought, I did," Gonzalez-Dippel remembers. She went on to win her race, and served on the Council from 2000-2006. Trouble always seemed to be brewing, however, as Floresville Council meetings became "the best show in town." From the very beginning, she says, "There were clashes among everybody--everything was disorderly--there was standing room only." So I told myself, 'After this, I'm done.'" But after watching continuing council deliberations, another observer encouraged her to do something about the impasse. "Somebody said, 'Maybe you ought to run for Mayor,'" she says. "And I thought, 'Maybe I should.'" She did run, won her race, and served in her term for 7 1/2 years, from 2016-2024. Approaching problems from a practical standpoint and drawing from that old Gonzalez Never-Give-Up philosophy, Gonzalez-Dippel says she set herself to ordering city government and insisted on decorum at public meetings. "I've always been a person who likes to get things organized, and that's how I approached it," she relates, "Just really straightforward." She also learned how to use the power of her office to keep things on even keel. ""I learned to use the gavel," she asserts, "and in the meetings, I'm pretty strict. I pushed for a policy of decorum, to keep things orderly. And I also make sure I don't get out of control myself." Eventually, much of the negativity Floresville was burdened with grew into the court struggle we reported on earlier in this piece. But Gonzalez-Dippel held firm in her leadership and avers her success in part is due to women's, and her, special approach to governing. "Look. It shouldn't just be a man's world," she declares. "As a woman, you see all these things that need to be changed, and you worry about the safety of the people. Women are like that." She enthusiastically urges other women to get into the ring, asserting, "I'm proud of women stepping up to do this job. There are lots of women who are strong enough to do it. "As for my own reasoning, I looked at everything going on, and I thought, 'If I don't do it, who will?' "And when things would get really bad--and lots of things did--I just said, 'I'm not giving up.' And then I look to God for strength."

| ||

|

"I became a pariah for a time" Leander Mayor Christine DeLisle |

|

| Leander Mayor Christine DeLisle, who came to Texas with her husband from Hayward, California, says she came with two assumptions: local people in the small town bordering Austin where she moved were going to be liberal; and she "would never want to be in politics." Time and experience proved her wrong on both counts. "First, I've got some conservative tendencies myself," she asserts, "so none of that mattered one way or another." Following in her career law enforcement father's footsteps and majoring in Criminal Justice at the College of San Mateo, DeLisle is quick to announce her "no politics" goals in life at the time. "Basically, I got the Mrs. degree, was devoted to two beautiful kids, and couldn't have been happier with my choices. I had no interest in politics at all," she declares. Then DeLisle, on getting settled in Leander, noticed the town didn't have many places where children could pass time and recreate. "I eventually got involved in the PTA where my kids went to school--and I heard about plans for a Rec Center that hadn't happened yet. I couldn't figure out what was stalling that." Hearing complaints city management hadn't taken enough leadership in getting the center rolling, DeLisle says she resolved to find out what was delaying the project. "Honestly, this was about my kids--everything is with me," she explains. "I wanted my kids to have a place to hang out and be safe." So DeLisle began to find out facts, and started talking to the locals. "I just have to open my big mouth--I'm Italian for gosh' sakes," she quips. "I just wanted to help out. And I had a few ideas--I always see an opportunity to get something done." DeLisle's ideas, she says, contrasted with those in city office. "Some people had issues with the City Manager, and I would start speaking up at meetings because I didn't like the direction the bond issue was going," she says. Over time, the center continued to be discussed, but plans were stalled--it is still in the planning stage and hasn't been built yet. DeLisle in 2017 went on to become a member of Leander's Economic Development Committee, and in 2018 chaired the Charter Review Committee. The same year, DeLisle's vocal presence in those groups and at bond election hearings and other community meetings began to draw the attention of others, some of them defending the local status quo. "Finally somebody said, 'Well, If you think you can do better, maybe you should run for City Council.' "This really hit me as something unthought of," she says. "I never imagined being in politics--I try not to even think about politics." But DeIisle thought more about it, and launched a campaign. Winning her race against an incumbent with 62.9 percent of the vote, she went on to serve a three-year term in Place 4 on the Leander Council, and credits her success to a voter base other politicians may not have thought of. "My election base was moms, women like me with kids," she notes, with whose challenges raising children she closely identifies. DeLisle continued on as a city Councillor, serving, among others, her constituency of young families. She says she labored tirelessly, and was proud of her work. Then the gay thing happened. In July, 2019, after having agreed to host a "Drag Queen Story Hour," directors at the municipal library elected to cancel the event in the aftermath of outside resistance and threats. DeLisle's church, the Open Cathedral Church, then moved to host the event, now renaming it a "Family Pride and Story Time," and renting a meeting room at the library for the purpose. DeLisle and another church member attended the event and read stories to children who attended, but tried to keep a low profile. "I went in through the back," DeLisle says. "I didn't want it to be about me--I wanted it to be about the people affected." That strategy ultimately didn't help, she opines, owing to decades-long cultural values conservative Texans hold to. "I became a pariah for a time," she remembers, with some emotion. "But for me it was pretty simple--I wanted the people to know not everyone was against them." In the months preceding the library event, DeLisle says she had already begun to interface with those in the area's gay community. "As I always did, I had moved around and through the community, talking to everybody I could--I wanted to know first hand what people needed, what they might be going through, to give them support," DeLisle relates. In those one-on-ones, DeIisle says she heard some gay residents mention they felt uncomfortable and unsafe in the community. At the same time, she adds she couldn't help but notice when some local residents harassed members of the LGBTQ community. "I just didn't understand that behavior," DeLisle interjects. I said, 'It's 2019 now--how can that even be a thing?'" The new Council member now took up the cause with resolve. "'I thought, 'I am going to own this,' she declares. "I'm a new Texan, but I'm going to be involved." She continued to be touched by local residents--some of them very young--who were struggling with their sexuality and affectional preferences. "Some of them would tell me, 'I felt like I didn't belong here,'" she mused. "And that really made me sad. So I stood out for them." With time, she says she's confident values will change. "A lot of it was generational--the kids just don't care. I've come to realize we're in a culture war--and young people's voting trends are different from generations older than them." Over time, DeLisle also weathered the storm, continued to serve, ran for mayor, and was subsequently elected over an incumbent on May 1, 2021, to become the city's youngest, and second female mayor. She adds her win also affirms her belief a cadre of capable women like herself coming into local office in greater numbers will bring vital change to Texas. "In Leander, as an example, we have a majority female Council," she declares, adding, "and being a woman governing today, it's no big mystery: You just have to be stronger and tougher and better."

| ||

|

"I don't beat around the bush--I say what's on my mind" Schulenburg Mayor Connie Koopmann |

|

| "I'm a full-blooded Bohemian!" Schulenburg Mayor Connie Koopmann proclaims, standing up front and forthright in her ethnicity as a member of one of Texas's largest and most dominant cultural enclaves, the Czechs.² Koopmann's identity as a Czech-Texan strikes you right away, embodying as she does the social magnetism her people have come to be known for: the gregarious social greeting, the hearty laugh, the hard-working, hard-playing take on life: happy people content and comfortable in their largely agrarian, provincial way of life. Much that Koopmann does and says seems to hearken back to her local community's distant origins, when a few brave souls, fleeing the violent peasant revolts against European monarchies in 1848, grasped what little they had, left their homes in Bohemia and Moravia, and sailed over harsh seas to reach America and a better life. Booking passage aboard rickety, sail-powered wooden ships--some as small as 60 feet--and enduring sometimes three- and four-day journeys over a cold and stormy Atlantic, Czech peoples at length reached American shores, and the amenable ambience of settlements like Schulenburg. And as they set about establishing their new communities, they drew from traditions they grew up with in the Old Country. "We support and promote the many things that make Schulenburg unique, and that make us stand out for the old traditions," Koopmann asserts. "Like our Texas Polka Museum." The long-time mayor refers to her town's annual polka music festival, sponsored by the museum, that draws performers from all over the country and showcases a style whose Old World song-forms originated in Europe: the Polka and other folk genres. When 19th-century Czech, German, Moravian, and Polish settlers established communities in Texas, their musicians brought a European instrument--the "button" accordion³--with them, and continued to play songs their people could dance to: not only the Polka, but the Mazurka, Schottische, Vals (Waltz), Redowa, and others. Mexican musicians in the region, originally coming up from Mexico, also played the instrument, giving a bit of Tejano "flavor" to the tunes, and in time adapting their own popular Huapango and rural Cumbia to the new accordion-based style. At the same time, Cajun players from neighboring Louisiana, who played the same accordion, came over to jam in their own Creole-laced style and make money on weekend gigs. Players from these diverse traditions learned from and influenced each other--and the result was the dazzling cultural mix of musical styles Texas and towns like Schulenburg are famous for. ³(Texas accordion players in these styles, then and in more modern times, favored instruments made by Continental craftsmen like Italy's Gabbanelli, whose instruments had a rich, but percussive tone and clean, crisp action; and Germany's Hohner, also a maker of popular harmonicas.) Czech music and dance are not the only cultural markers that are part of her small town's artistic appeal, Koopmann stresses. "We feel deeply reverent here about our famous Painted Churches, and I don't think there's anything more beautiful anywhere," Koopmann declares. These area churches, most of them serving Roman Catholic worshipers, were built in such settlements as Schulenburg by Czech and German immigrants in late 1800's and early 1900's in a style similar to those of their homeland, and feature statues of angels, adornments in marble-like stone, hand-painted sculptures, and filigree designs in a myriad of colors, shimmering in the glowing light of multiple stained glass windows. The churches are a spectacular thing to see, and the Schulenburg area's St. Mary's Catholic Church, called the "Queen of the Painted Churches," is breathtaking to behold. Schulenburg's other culture-ways aside, Koopmann suggests there is another Czech tradition that attracts visitors in droves. "Don't forget the bread," she exclaims. "Czechs make the best bread in the world, I mean, those kolaches!" Oh, yes, the kolaches, the strudels, the klobasniky, not forgetting the sausages, the slow-smoked brisket, those Czechest of all good things--anybody from Texas knows, you want to eat well, go to Schulenburg, or Hallettsville, or West, or Ennis--or ... anywhere there's a Czech doing the cooking. True to her Czech traditions, this daughter of Schulenburg, originally a Janacek, counts the consummate skill of bread-making as an important part of her early life. "My family had a bakery here, and I worked there throughout my early life and school years," Koopmann remembers. "Then, when my folks retired, I went on and ran it. It's one thing that gave me my business experience. I've spent a lifetime in business, in fact." Now a busy caterer, Koopmann also works at the local school district and says she "has always been interested in politics." That interest led her to serve on the Schulenburg City Council for four years, and to campaign for Mayor In 1997. "I decided to run for mayor, and I won," she reports, an achievement that made her the first woman, and youngest mayor in the city's history. Her intrepid style and pragmatic approach to governing have led to some critique, she admits, but also garnered respect from her constituents. "When I started, my Council was five gentlemen--plus me," she relates. "Everything I did, they shot down." To that kind of opposition, Koopmann quips, she had the perfect comeback. "So I would say, 'God put more women on earth because He knew they would get the job done," she laughs. And she came to prevail, learning from any mistakes her inexperience may have caused. "I was green when I started, and my first term was tough," Koopmann recalls. "I learned a lot." Koopmann says she succeeds at her job by remaining straightforward. "I don't beat around the bush," she declares. "And I think people like that." Right out of her revered cultural milieu, Koopmann continues to dash about, ever the champion of her town, working tirelessly to ensure Schulenburg folk enjoy the benefit of an efficiently-run city government. But she is, after all, a Czech woman, as robust and lippy as they come. And as many have already found out--you really don't want to mess with that. "I shoot from the hip," Koopmann declares, "in a speech, in Council, I don't use a script--I just say what's on my mind."

²The 2000 census shows Texas is home to nearly 200.000 people of Czech descent--the largest Czech population in the country.

| ||

|

"I HAVE to be assertive--I'm short" Saint Hedwig Mayor Dee Grimm |

|

| Caught in her blue-eyed, laser gaze, you immediately feel the intense verve that propels

Saint Hedwig Mayor Dee Grimm, who came to her office with a portfolio of major professional achievements: She is a Registered Nurse, attorney, Emergency Medical Technician, Municipal Court Judge, United States Air Force veteran, published journalist, and long-time practitioner of Okinawan Shorin-ryu karate. For all that, Grimm almost dismisses her accomplishments: "I have to be assertive," she laughs. "I'm short!" She'd graduated from journalism school after fulfilling her tour in military intelligence with the U.S. Air Force, and had worked for eight years as a freelance journalist, following up with law school and a J.D. degree in 1980. Her years in the practice of law, she says, left her wanting something more, something more inherently humane. "I always knew I wanted to be an Emergency Room nurse," she says, and acted on that ambition by attending nursing school in Hawaii, earning her R.N. degree there in 1990, and paying for her schooling by working part-time as an EMT. She became fully engaged in emergency medicine, she notes, and learned to channel her desire to help others with the skill to intervene and save lives. "When you see someone in an emergency setting, you have to realize--this is the worst day of their lives," she declares. "To be effective, you have to learn the difference berween sympathy and empathy. Emergency situations taught me how to do that." But life brings even the strongest among us life-changing experiences, Grimm included, and in the middle of a thriving career, she endured a major setback. "I was a marathon runner," she says, "and spent years in karate, and all that beats up your body. But even those two things couldn't compare with the horses." Grimm had become a passionate advocate for mustang rescue in Nevada, and made the decision to adopt her own mustang from the area Bureau of Land Management, with plans to rehabilitate the animal. But things didn't work out as she had expected. "I got the mustang for $300," Grimm says, "but one of my attempts to ride it turned it into a $30,000 animal--which is what it cost to treat injuries to my spine afterward." Because of her experience with the mustang and its aftermath, the mayor now consults with medical professionals who aid the disabled, and intervene in disaster situations. "Disaster doesn't discriminate," she says, "but society does. So we in the field have to learn how disasters affect people with disabilities, and respond more effectively." Unlike everyday emergency medicine, Grimm says "disaster response is quite different from emergency response in a hospital settling. In the latter, you usually have everything you need--equipment, medicines, and the like. But in a disaster situation, you don't." She shares her expertise in disaster response as a consultant to hospitals and first responsers which may have to deal with mass casualty situations, and that background also helped her usher Saint Hedwig through the 2020 outbreak of the Covid virus. "If anything, Covid showed me we were ill-prepared," she warns. "And the long, difficult consequences of the appearance of the virus threw us into a long learning curve. We know lots more now." In her tenth year as mayor, in keeping with her background in jurisprudence, Grimm also serves her historical Texas city as its Municipal Court judge. Saint Hedwig originally was settled in 1854 by Polish immigrant families from Silesia who came to South Texas with few resources, but big dreams, and set to work building a community after purchasing 777 acres of an area plantation in the San Antonio region. The new Texans, most of whom were Roman Catholic, also built and established a church, made of sandstone, and named their town Saint Hedwig, honoring the patron saint of their Silesian homeland. The church was named The Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. With a reputation for tolerance, Saint Hedwig's early inhabitants knew nothing of slavery, and after the Civil War welcomed slaves who had been freed from southern states and slave-holding regions of Texas, some nearby. Through the 19th and much of the 20th century, church records show Saint Hedwig was the state's largest Polish parish. Incorporated in 1957, and with a 2020 population of about 2,500, Saint Hedwig's community life and economy is still based, as in its early years, on agriculture. For her part, the town's ever-moving mayor, whose past life has included many a port-of-call, says she is "settled in" and happy with her place in its history. "I'm the luckiest mayor in the world," she exclaims. "We're in an agricultural environment, where people are proud of their heritage--and I'm privileged to serve them." | ||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||